~the goal of this blog is to critically question, respond and encourage dialogue regarding the global perspectives on the varying meanings and forms of literacy and literature available to children, families and educators~

Wednesday, March 30, 2011

Re-defining Literacy...some final thoughts

My definition of literacy hasn’t really changed all that much; however, my awareness of how it is expressed, how it is practiced, and how I'm “teaching” it has definitely changed, perhaps even heightened. I’m finding that in my interactions with children I see literacy “in-the-making” beyond the fact that they are using crayons, pens, and paint on paper. I now see that it’s in the play, interactions, and conversations they have with each other and with me. This has definitely changed the way I approach literacy with the children. However, I still think about the conventional practices in the schools and what happens after they’ve been with me. I think about how much I’ve actually prepared them for that experience, if I have altogether. I also think about whether I have done enough writing or reading with them or have exposed them enough to these literacy practices to prepare them for what is going happen in the classrooms, what will be expected from them. Is the emergent way I’m looking at literacy enough to prepare them for that? Even as I try to separate myself from that conventional way of thinking and practicing I just can’t help but think how backwards literacy practices are in the school system, how limited literacy practices are encouraged for children, and how profoundly influenced I still am of its very practices.

Children as Writers

I don’t have a very clear memory of when and how I began

making scribbling marks or writing as a whole. What I do know quite clearly is my affinity for the varying

techniques used to write (i.e. calligraphy, learning and practicing about other

fonts/styles, etc.). I believe

that for me growing up, writing wasn’t about expressing or communicating

thoughts and feelings but it was aesthetically motivated – if I had to write,

it had to look ‘pretty’, neat, and very legible. I wasn’t focus too much on the content. I believe this is influenced by

interactions with my family. My

grandfather, who was an art teacher, had a 4-5 foot green chalk board in our

dining room and every morning he would write out the date and the number of orders

(they sold blocks of ice) they had for that day. I loved his penmanship and there were times where I would

closely observe him write with careful precision on the chalk board. It was the same experience with my mom

and how, when she wrote out letters or note cards, she would spend the time to make

sure each letter was done right.

In my elementary school years, I think I flew below the radar when it

came to assessing my writing and reading skills because my writing was legible enough.

I think that because of this, the

content, spelling and grammar wasn’t overly focused on. I remember getting a report card saying

that I needed to work on my storytelling and a few grammar skills but my

spelling and the legibility of my actual writing style was enough to grant me

‘satisfactory’ in my overall language arts skills. From this I think about other possible experiences of the

legibility or illegibility of one’s writing as influencing how that child is

thought of as a whole.

I can recall a ‘forced’ reading/writing or literacy situation experienced

by my childhood friend. During

“language arts” period we were often given notebooks in which half of each page

had a space to draw images/pictures and the other half was lined to write out

the story behind these drawings.

He always drew but the written part was always minimal and ‘messy’ (a

term my grade 3 teacher actually used to describe my friend’s writing). As a result, he would always be set

aside by the teacher, and in turn, always asked him to “elaborate” the written

part of his story and also work on improving his writing so that it could be

easily read. Not only did he feel

embarrassed for being set aside, but he was also being forced to do something

that he did not connect to. Was he

not a good storyteller because he couldn’t articulate with words written on a

page? Did the teacher see him as lacking

(intellectually) because his writing was ‘messy’? When we played outside of the school walls he had elaborate

ideas and stories to attach to games which ranged from playing with toys and

other materials or “driving” to varying places in his dad’s old truck. Looking back on it now, he was more of

a visual, verbal, physical learner and reading or writing just wasn’t his

forte.

In reflecting on my experience and my observations of my

friend’s experience, I relate this quite well with Barrat-Pugh’s (2007)

assertion that “literacy practices are differently valued in different

contexts…in educational contexts, certain forms of literacy become privileged”

(p. 137). In my situation and

clearly in what I’ve seen in my friend’s situation, reading and writing was

significantly valued more than other literacy practices. Therefore, other practices were not as

honoured and in turn held children back and limited their ability to express,

explore and understand themselves in their world.

Logue, Robie, Brown, and Waite (2009) suggests that “[i]f all

children are to become successful readers and writers, teachers must approach

the teaching of literacy skills by using the skills and dispositions that

children bring to the learning experiences” (p. 221). Perhaps, my friend would have enjoyed writing better if our

teacher closely observed what his literacy strengths were and incorporated that

with the process of learning to write with “elaborated content” and legibility. Barrat-Pugh (2007) states that

“learning and teaching writing is complex and multifaceted” but more often than

not, especially when reading and writing is the dominant discourse of literacy

practices, educators and even parents approach literacy learning as though it

were “a linear process in which children progress through a series of stages”

which can be implemented and therefore mastered with drilled repetition and memorization or letters/symbols and words/phrases. It can and does work, as articulated by

Wong (2008) in her study with preschool children learning how to read and write

in Hong Kong. However, I can’t

stop thinking about the children who have significant difficulties with

mastering reading or writing or those who require more time (beyond the

prescribed school year). Will they

be left behind if their stories aren’t interesting or creative enough or

because their spelling or writing styles aren’t just up to par?

I end this entry by highlighting another suggestion of how we

can possibly engage in a balanced approach to teaching children literacy

skills. Wong (2008) suggests to “create

learning environments that are realistic and relevant to learners, and support

learning through multiple roles” (p. 116) and multiple modalities. In my workplace and in my community in

general, I see children coming from varying cultural and social backgrounds and

I believe that Wong’s (2008) - and even Logue et al., (2009) – suggestion[s] is/[are] very crucial to consider and allows our practice to be more ethical as a result.

References:

Barrat-Pugh, C.

(2007). Multiple ways of

making meaning: children as writers.

In L. Makin, C. Jones Diaz, & C. McLachlan (Eds.), Literacies in childhood: Changing views,

challenging practice (2nd ed. pp. 133-152). Marrickville, NSW: Maclennan &

Petty – Elsevier.

Logue, M., Robie, M., Brown, M., & Waite, K. (2009). Read my dance: promoting early writing through dance. Childhood

Education, 216-222.

Wong, M.

(2008). How preschool

children learn in Hong Kong and Canada: a cross-cultural study. Early

Years, 28(2), 115-133).

Saturday, March 19, 2011

Multiliteracies

When I think about multiliteracies as referring to the “multimodal ways of

communicating through linguistic visual, auditory, gestural, and spatial forms”

(Hill, 2007, p. 56) I think about how this can accommodate the different ways

that children engage and express themselves and the meanings that they make

about the world around them. To

understand literacy as something that is beyond the practice and skill of

reading and writing is significant because children do have literacy practices

that are not limited to these two traditional skills. “Children in early

childhood have always used construction, drawing or illustrations, movement and

sound to represent meaning. The

newer multimodal technologies add to children’s choice of medium to represent

ideas and to comprehend the meanings in a range of texts” (p. 60). In my work with younger children who

are pre-readers and pre-writers, I have seen them express themselves within

such an array of actions (dancing, gestures, oral storytelling, etc.) and

creations (arts and scribbles, constructions, etc.) and to have to limit them

to express themselves or make meaning of their surroundings with a small set or

specific set of methods seems unethical and harmful for the possibilities of

their potentialities. Also,

children are increasingly being exposed to digital literacies at home or even

in the communities (in libraries, stores, even in centres and schools) that the

literacy practices that they are learning from the exposure and engagement with

varying digitized mediums cannot be ignored.

Reflecting on the

modality of movement, I think about the children whom I’ve worked with who are

more comfortable expressing themselves and exploring their space (and the

people and things within it) in a more physical sense. These children “use their bodies to

make meanings that are sometimes difficult to represent accurately in written

form” (Makin & Whiteman, 2007, p. 171) and even in verbal form and to restrict

them to express themselves in these ways often becomes problematic for them. In many situations, when these children

are limited (or ‘encouraged’) to simply say what they are feeling or thinking

but they don’t know how to verbally articulate it, they get confused and

frustrated and as a result, ‘act out’.

Makin and Whiteman (2007) articulates that,

Throughout movement, it is

possible to explore feelings, expression relationships and configurations that

occur in everyday life in quite different ways than in using written words

…

[movement] extends the

resources at their disposal to use oral and written language and to develop multimodal

ways of communicating (p. 172).

They provide a possible way of

seeing movement as a means for children to “communicate” and educators, adults

altogether need to recognize the merits of physical actions in revealing what

children are trying to express or how they are understanding themselves and

their environment. Young (n.d.)

emphasizes this further and states that with movement such as dance, it is “to

enter another world of language and literacy” (p. 15); a “non-language way of

making meaning” (p. 5), all of which acknowledging movements as important modes

of expression and exploration and fostering learning and enhancing literacy skills as a whole.

Overall, Hill (2007) also encourages

us to take a balanced approach when we are teaching children literacy skills

but also emphasizes the importance of learning and understanding the literacy

strengths that each child has so that s/he is not left feeling frustrated

because they cannot express her-/himself.

References:

Hill, S.

(2007). Multiliteracies:

towards the future. –

Makin L. & Whiteman, P. (2007). Multiliteracies and the arts. In L. Makin, C. Jones Diaz, & C. McLachlan (Eds.), Literacies in childhood: Changing views,

challenging practice (2nd ed.). Marrickville, NSW: Maclennan & Petty – Elsevier.

Sunday, March 13, 2011

Critical Literacy

The new technologies that seem to symbolize

and support globalization processes, give a previously unavailable power to

individuals with access to them.

Through technologies such as the Internet, individuals (including

children) can mediate or transform their own understandings without the support

of traditional mediators like teachers, parents, or governments (Kennedy, 2006,

p. 298).

I chose to start with this statement for the fact that more

and more children are able to easily

access the “technologies” that Kennedy (2006) speaks of in this statement. If it’s not the computer or the

internet, it’s the television, radio, or simply in the very literature that is

available to children. What provoked

me further is within the line, “individuals (including children) can mediate or

transform their own understandings without the support of…teachers, parents, or

governments”. Initially, I

questioned why would it be so bad to think in these terms? Aren’t we supposed to see children as

autonomous beings, capable of thinking, acting, and deciding for themselves

without any influence from the adults who most often control and dictate how

children should live in general?

However, I began thinking about the materials that are out there and

how, in many cases, racist, sexist, elitist (to name a few) ideologies are

implicitly and explicitly promoted in the digital materials available to

children. It speaks to the idea of

just showing one dimension, one story usually that of a dominant group (Westernized,

white, English speaking, middle class…?)

Do children have the ability to be critical about what they are seeing

or hearing if they are always exposed to such one-sided “popular media” (Jones

Diaz, Beecher & Arthur, 2007)?

If we respond with a ‘no’ to this question does it then justify the roles

of the adults to come and help children learn how to be critical?

For the purpose of this discussion, let’s say that children do

need guidance in critical literacy practice. I know how problematic taking this stance is altogether, but

let’s focus on the fact that the practice of critical literacy is necessary for

the very reason that a lot of the materials that are out there targeting

children’s impressionable minds are propagating inequities, stereotypes, and discrimination

of individuals or groups. Jones

Diaz, Beecher, and Arthur (2007) seems to provide an enhanced (perhaps, a counter-)

argument from the statement I started with, which also justifies the necessity

of children learning why and how to critically analyse what they are seeing,

hearing, reading and so on. They

state,

[r]ather than leaving children and young people

to mediate their own understandings of gender, ‘race’, ethnicity and social

power through interactions with texts of popular culture, educator involvement

can enable ideological and consumer issues associated with popular culture to

be problematized. Educators can

support children to critically examine the ways that dominant discourses are

perpetuated in texts of popular culture.

They can assist children to engage in resistant readings and to produce

alternative texts (Jones Diaz, et al., 2007).

I

believe that there is little control or authority placed on the teacher over

children, rather, children are empowered to see the otherness or what’s possibly

missing within the materials they are exposed to in the “popular media”.

It is

important to note, which Jones Diaz et al. (2007) also emphasize, that we need

to acknowledge why children are drawn to the materials they are exposed to and

how they are interpreting it altogether. I think that with this practice, it highlights

the importance of engaging in an ongoing conversation between children,

teachers, parents, and other community members. It is also important to engage

in such conversations with children regarding the need to be critical because

of what they themselves can proliferate in their actions.

References:

Jones Diaz, C., Beecher, B. & Arthur, L. (2007). Children’s worlds: globalization and critical literacy. In L. Makin, C. Jones Diaz, & C.

McLachlan (Eds.), Literacies in

childhood: Changing views, challenging practice (2nd ed. pp.

71-86). Marrickville, NSW:

Maclennan & Petty – Elsevier.

Kennedy, A.

(2006). Globalisation,

global English: ‘futures trading’ in early childhood education. Early

Years, 26(3), 295-306. doi:

10.1080/09575140600898472

Saturday, March 5, 2011

First Nations Literacy Practice: Oral Storytelling Tradition

Responding to this week’s readings gives me the same feelings

of uncertainty and lack of confidence in my thoughts which I had with the

discussion around cultural authenticity.

I feel this way because I haven’t read too much First Nations’

literature and while I have taken courses in First Nations/Aboriginal studies

in the past, I feel anxious about discussing the process and subject matters

related to First Nation’s stories. Why could this be? Is it due to the fact that I’ve had limited exposure to it

or because First Nation literacy practices and literature is not fully

introduced and discussed in the curriculum of all of my educational

experiences?

Thomson, M. (2007). Honouring the word.

Tribal College Journal, 19(2).

With First Nations stories, I feel that it is meant to be

listened to and not be analysed or critiqued. I say this not with the idea that critical analysis should

not be done at all on the stories told.

However, given that First Nations people have long been silenced and

continue to struggle to have their voices and stories heard and told, simply analyzing their varied and complex stories is propagating colonizing

tactics of control and suppression.

Thompson (2007) highlights the value of “open dialogue” and quotes an

elder who emphasize the “value of listening” and the “trust” that is needed “to

listen well” (Yellow Hawk, as cited in Thompson, 2007). From this I see the process of an

ongoing conversation between the storyteller and her/his audience and the

importance of listening (from all angles) as a significant piece in the process

of storytelling as a whole. First

Nations people value the knowledge that elders profess in their stories and

also what “younger people, even children” (Thompson, 2007) have to offer in the

stories they listen to. Oral

storytelling traditions bear significant knowledge, “a distinctive intellectual

tradition” (Moayeri & Smith, 2010, p. 414), that challenges beliefs of the inaccuracies

and illegitimacies within oral stories, “oral histories” (Thompson, 2007). “Scientific Knowledge” is but a single

story and just as we’ve been encouraged to see that there are multiple stories

it is important to acknowledge that “traditional knowledge” will have its

merits (Moayeri & Smith, 2010, p. 415).

In reflecting on First Nations’ oral storytelling traditions,

I am reminded by my own experience with oral storytelling and the value that I

have for it. I think about other

cultures that strongly value this literacy practice in varying and complex ways

and relate it to Thompson’s (2007) words:

The oral tradition represents ‘the other

side of the miracle of language’…’the telling of stories, the recitation of

epic poems, the singing of songs, the making of prayers, the chanting of magic

and mystery, the exertion of human voice upon the unknown – in short, the

spoken word’…[the oral tradition is] a literature ‘of the people, by the

people, and for the people’ (Thompson, 2007).

I am

particularly drawn to the idea that oral storytelling traditions express

stories and “literature [that are] ‘of the people, by the people, and for the

people’”. I believe that it is

very fitting to the nature of its practice.

Conversely,

I also think about how this very practice is not always honoured and therefore,

practiced to its full capacity in our Westernized education system,

different literacies are privileged in

different institutions, which are controlled by a dominant power in each

institution….literacy is most often taught in schools as decontextualized,

technical skills…this disconnect between school literacy and home/community

literacies is holding back literacy development for children, particularly those

whose home literacies are undervalued and ignored by the schools (Moayeri &

Smith, 2010, p. 409).

Literacy

is still very heavily defined and practiced by the process of reading and

writing and this significantly challenges, perhaps to the extreme of eradication

of First Nations’ literacy practices of oral storytelling. What can become of these people and

other people who value this way of telling stories or passing on their

traditions, beliefs, and so on?

We’ve seen children struggle or be left on the margins feeling confused

or defeated when their learning styles and literacy practices are ignored. How can we be ethical and honour their literacy

particularities so that they are thriving instead of failing?

Thompson

invites us to think about how “the oral tradition could be fundamentally

superior to written literature or that texts that privilege the Indigenous

voice might speak more powerfully to Native students than literary

masterpieces” (Thompson, 2007).

Moayeri and Smith (2006) encourages us to “familiariz[e] ourselves and

valu[e] the diverse and multiple literacies that students of different cultures

bring with them [which] enhances the learning potential of those students and

that of the entire class” (p. 415).

They further provoke us to act on “diffusing the dominant power by

creating opportunities for learning about multiple cultures by deconstructing

existing [Westernized, white, middle-to-upper class, predominantly male

perspectives] text, using materials, or by viewing curriculum through a broader

lens” (p. 415). These are just

some possible yet very important suggestions to consider.

I end

this entry by repeating the questions raised by an anonymous contributor in A broken flute (Seale & Slapin, 2006)

because it speaks to the ethical practice which is necessary to consider

especially when working with children:

Will you help my child learn to read, or will you

teach him that he has a reading problem?

Will you help him develop problem-solving skills or will you teach him

that school is where you try to guess what answer the teacher wants? Will he learn that his sense of his own

value and dignity is valid, or will he learn that he must forever be apologetic

and try harder because he isn’t white?

Can you help him acquire the intellectual skills he needs without at the

same time imposing your values on top of those he already has? (Seale &

Slapin, 2006, p. 9)

References:

Moayeri, M. & Smith, J. (2010). The

unfinished stories of two First Nations mothers. Journal of Adolescent

& Adult Literacy, 53(5), 408-417.

doi:10.1598/JAAL.53.5.6

Seale,

D. & Slapin, B. (Eds.).

(2006). A broken flute. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press & Oyate.

Saturday, February 26, 2011

Literacy and Cultural Authenticity

-The following entry is written as a response to the week's provocations/questions provided by K. Kenny-

(K. Kenny)

My first question that I would like to put to you is how do we know when a book is culturally authentic? Susan Guevara (2003) argues that an authentic work is one that feels "alive" and it is something that cultural authenticity is related to the way the reader interacts with the books. She states, "What is cultural authenticity? I believe if we look to what rings true for each of us as individuals; if we look to what we see ring true for our students and colleagues, this is a good guideline" (Guevara, p.59). It is that feeling of trueness for the reader that is important. Seeing an affirmation of ones lived experience is a way to judge cultural authenticity.

Check out this blog by someone serving on the Children’s Literature Assembly for the National Council of Teachers of English Committee for Notables Books in English Language Arts.

What happens when you believe that a work is culturally authentic? If you are coming from an outside culture, and have no firsthand knowledge of a culture are you able to feel that "trueness?" What if that story contains stereotypes that you are unaware of?

Is "cultural authenticity" defined subjectively? I asked this question because while the idea of culture can be defined in a collective sense, the experiences within can be personal and be very subjective. When Guevara (2003) states that authenticity of literature and arts lies in its ability to provoke the feeling of "aliveness", "emotional intuitive connection" and an "affirmation of...existence" (p. 57-58), I feel that these are or can be very subjectively defined. When I read Rohinton Mistry's (1995) A Fine Balance, I can confidently say that I felt these features but I cannot confidently admit that from here I now know enough about the Indian culture. If I had read more of his work or other stories of the same genre would it change this? Will it equip me with more information about the culture to warrant that I can say that it is authentic enough?

It is a challenge for me to claim a written or an art piece to be culturally authentic and I question the existence of review panels (one that is referenced in your provocation and by Alison from NV library). As I've asked previously, does the question of cultural authenticity a safety/protective/or corrective measure which makes sure that cultural ideas/traditions/beliefs are expressed/portrayed in a politically correct way so not to "offend" those in the culture or others in general? A line in your provocation also speaks to this questioning, "no matter how imaginative and how well written a story is, it should be rejected if it seriously violates the integrity of a culture”. I wonder if this is more directed to an "outsider" writing about a particular culture or of an "insider" who is expressing their own experience of their culture. I see the merits of the statement presented but would it be fair to silence ones thoughts and experiences, especially if it is that of an "insider", because it challenges the culture's integrity? Or is the focus or the analysis of cultural authenticity simply a way for observers or readers (insiders or outsiders of a culture) to critically think about what they are reading or seeing so that they don't become victims of the dangers of a "single story" (Adichie, 2009)? Short and Fox (2003) seems to affirm this when they say that, “the discussions [of cultural authenticity] invite the field into new conversations and questions about cultural authenticity instead of continuing to repeat old conversations” (p. 22). Is the idea then to create and encourage critical thinkers and readers so that they are open “to other points of view” and promote “democracy” and “social justice” (Short and Fox, 2003, p. 23)?

(K. Kenny)

Many of you have watched the video, The Danger of a Single Story but please take another look, and think in terms of cultural authenticity. She tells of the fact that a professor tells her that her novel is not 'authentically African' because the characters do not behave in a way that he is used to. He had a stereotyped view of Africa and her story did not fit that view. His was a single story.

At the library it was talked about when we see stereotyped images in books, such as a Mexican person wearing a poncho, and why was it not okay to have books with these images in it if that culture really does wear that cultural dress. I keep coming back to this idea of a single story. In our libraries we have so few books with Spanish, French, Italian, Mexican, Inuit, etc, etc people depicted. In the ones that we do see often the people are depicted a certain way. Thus we gain a single story of an entire culture.

Thoughts?

In your first question/provocation, I ended my response by asking whether questioning “cultural authenticity” is something that will perhaps, diminish or prevent the “danger(s) of a single story” (Adichie, 2009) – I think it is more relevant to ask that question in this discussion. Upon watching the clip and reviewing the readings, particularly Aronson’s (2003) A mess of stories, I think about some possible ideas he presents to answer my question:

if we take away the false certitudes of ethnic essentialism, if we are honest, rigorous, and thorough enough to look deeply at peoples myths and ways of life around the world, we will find….We have a mess of stories and then we write our own

….

we must be rigorous, attuned to the complexity of cultures, willing to recognize the limitations of our own points of view (p. 82)

Within the complexities are the stories that Adichie (2009) challenges us to tell and listen to:

people…are eager to tell…many stories. Stories matter. Many stories matter. Stories have been used to dispossess and to malign. But stories can also be used to empower, and to humanize. Stories can break the dignity of a people. But stories can also repair that broken dignity.

Does the question then change to not necessarily defining what is culturally authentic within one or each story but how (true) authenticity lies in the relationships/connections we have with the “many stories” or "mess of stories" (Aronson, 2003) that people of the world have as a whole?

Some other questions to consider:

~do we only question cultural authenticity in literacy (or even in art) or are we more provoked to respond and critically analyse cultural authenticity when it portrays an idea or image that might pigeonhole or stereotype a group of individual?

~is the attempt for literacy material to be culturally authentic the same as to be politically correct so that it avoids potentially “offending” someone or some groups?

~is the definition of culture authenticity a subjective one?

~who defines cultural authenticity - person/people from the particular culture portrayed in the literature?

~in order to prove the author or artist's claim for authenticity does s/he have to be subjected to questions on the validity of their cultural background?

References:

Adichie, C. (2009, October). The danger of a single story [Video file]. Retrived from http://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story.html

Fox, D., & Short, K. (Eds.). (2003). Stories matter: the complexity of cultural authenticity in children’s literature. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Mistry, R. (1995). A fine balance. Toronto, ON: McLelland & Stewart Ltd.

Mistry, R. (1995). A fine balance. Toronto, ON: McLelland & Stewart Ltd.

Tuesday, February 15, 2011

Literacy as Multimodal Meaning Making

(Written with M. Lawson)

Multimodality

speaks to the varying ways of representing, communicating and interpreting messages

transmitted between people’s interactions with one another, with symbols, with

objects and other materials that provoke meaning (Kress, 2003). Given that people come from diverse social

and cultural backgrounds, this has a significant influence in how a person or

groups of people represent and communicate how they make meaning of their world

(Kress, 2003, Martello, 2007; Seigel, 2006). Kress (2003) asserts that representation and communication

of ideas are no longer limited to what is written and read or spoken and heard. It is no longer limited to lingual practices

that only address two of our senses, sight and hearing; rather, it can be

expressed in multimodal ways that trigger other parts of our senses and enrich

our overall interpretation of things and situations (Kress, 2003). Literacy is a way to represent and communicate

an array of meanings and ideas that people have but it can also be described as

being multimodal in its own right. Children naturally experience

literacy in a multimodal way therefore, within

the context of educating and working with children, multimodal literacy is important

to acknowledge, analyse, and put into practice.

Kress (as cited in Martello, 2007) defines multimodal literacy as a variety of ways in which children explore and practice literacy. The multimodal practice involved in literacy learning is also significantly influenced by children’s diverse social and cultural traditions and practices. As a result, children’s literacy practices can range from being linguistic, visual, oral and auditory, gestural and physical (actions or touch, ex. braille), or a combination of some or all (Martello, 2007, Seigel, 2006). In the classrooms/centres, educators can support children’s literacy development by learning about the child and their literacy experiences at home and even within the community. As educators familiarize themselves with the children’s families and cultural backgrounds and practices, they can incorporate such practices in the classroom/centres in a more natural and ethical way. However, children are still taught with the expectation of mastering literacy by imposing letter sounding and writing drills or rote memorizations, following what Seigel (2006) describes as a “narrow and regressive vision of literacy learning in school[s]” (p. 65), which sets children to fail academically and be labeled “at risk” or worse, “illiterate”. These are the children who may not connect and are unable to thrive in these conventional literacy practices because of its limiting ways and because it ignores other possible ways that they do use to learn and engage with literacy. Failure to recognize children’s multimodal literacy learning and ignoring literacy experiences at home is a disservice to children and their overall development.

Educators can “have a positive impact on the emerging literacies of every child by achieving continuity between home and educational literacy practices” (Martello, 2007, p. 89). Multimodal literacy practices has a potential to meet every child’s needs, especially as they approach and learn to read, write, and generally express themselves through varying modes and mediums. If a child has difficulties expressing her/himself through spoken language, perhaps the visual or gestural mode will allow him to do so. “Embracing and capitalizing on a wide range of home and community literacy practices extends the learning possibilities for all children” (Martello, 2007, p. 101). The important task is to closely observe, be well informed of, and foster and support the child’s “literacy strengths” (Evans, 2001) so that s/he has a positive and meaningful experience with literacy learning. It is equally important that educators critically reflect on their own history with literacy practices to be able to recognize the uniqueness of literacy learning and therefore, enhance the way they engage in literacy practices with children.

Through our inquiry we reflected on our experiences in engaging with multimodal literacy and in supporting its varying ways with children. We questioned how our own social and cultural backgrounds influenced how we approached and encountered literacy as young children and whether we were encouraged to freely experience literacy in all of the ways we wanted to. We wondered how such experiences could have influenced how we approach literacy teaching and learning with the children we work with now. Finally, we questioned how we would promote multimodal literacy practices and also asked ourselves whether we use it more naturally or as a response to children who are not responding to particular literacy activity. Our experiences have been of both but we believe that this was a part of the process of being attuned to children’s multiple ways of learning and making meaning of their world. We surmised that we ourselves represented, communicated and interpreted in such a myriad of ways that it is wrong to restrict oneself, and therefore to restrict others – children – to make meaning within limiting or simplified terms.

Kress (as cited in Martello, 2007) defines multimodal literacy as a variety of ways in which children explore and practice literacy. The multimodal practice involved in literacy learning is also significantly influenced by children’s diverse social and cultural traditions and practices. As a result, children’s literacy practices can range from being linguistic, visual, oral and auditory, gestural and physical (actions or touch, ex. braille), or a combination of some or all (Martello, 2007, Seigel, 2006). In the classrooms/centres, educators can support children’s literacy development by learning about the child and their literacy experiences at home and even within the community. As educators familiarize themselves with the children’s families and cultural backgrounds and practices, they can incorporate such practices in the classroom/centres in a more natural and ethical way. However, children are still taught with the expectation of mastering literacy by imposing letter sounding and writing drills or rote memorizations, following what Seigel (2006) describes as a “narrow and regressive vision of literacy learning in school[s]” (p. 65), which sets children to fail academically and be labeled “at risk” or worse, “illiterate”. These are the children who may not connect and are unable to thrive in these conventional literacy practices because of its limiting ways and because it ignores other possible ways that they do use to learn and engage with literacy. Failure to recognize children’s multimodal literacy learning and ignoring literacy experiences at home is a disservice to children and their overall development.

Educators can “have a positive impact on the emerging literacies of every child by achieving continuity between home and educational literacy practices” (Martello, 2007, p. 89). Multimodal literacy practices has a potential to meet every child’s needs, especially as they approach and learn to read, write, and generally express themselves through varying modes and mediums. If a child has difficulties expressing her/himself through spoken language, perhaps the visual or gestural mode will allow him to do so. “Embracing and capitalizing on a wide range of home and community literacy practices extends the learning possibilities for all children” (Martello, 2007, p. 101). The important task is to closely observe, be well informed of, and foster and support the child’s “literacy strengths” (Evans, 2001) so that s/he has a positive and meaningful experience with literacy learning. It is equally important that educators critically reflect on their own history with literacy practices to be able to recognize the uniqueness of literacy learning and therefore, enhance the way they engage in literacy practices with children.

Through our inquiry we reflected on our experiences in engaging with multimodal literacy and in supporting its varying ways with children. We questioned how our own social and cultural backgrounds influenced how we approached and encountered literacy as young children and whether we were encouraged to freely experience literacy in all of the ways we wanted to. We wondered how such experiences could have influenced how we approach literacy teaching and learning with the children we work with now. Finally, we questioned how we would promote multimodal literacy practices and also asked ourselves whether we use it more naturally or as a response to children who are not responding to particular literacy activity. Our experiences have been of both but we believe that this was a part of the process of being attuned to children’s multiple ways of learning and making meaning of their world. We surmised that we ourselves represented, communicated and interpreted in such a myriad of ways that it is wrong to restrict oneself, and therefore to restrict others – children – to make meaning within limiting or simplified terms.

Some questions to consider:

~What is (or has been) your experience with multimodal literacy?

~How do or did your social (familial and community connections) and cultural backgrounds influence how you experience(d) multimodal literacy?

~How often do you actually engage in multimodal literacy?

~Do you use it naturally (2nd nature to vary the ways to introduce literacy experience to children) or do we use it as a response to children who are not as responsive to particular literacy activity?

~How would you try to overcome parents or other colleagues' resistance to multimodal literacy practices?

References:

Evans, K. (2001). Holding

on to many threads: Emergent literacy in a classroom of Iu Mien children. In E. Jones, K. Evans & K. S.

Rencken (Eds.), The lively kindergarten:

Emergent curriculum in action (pp. 59-74). Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Kress, G. (2003).

Multimodality. In B. Cope

& M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Multiliteracies:

literacy learning and the design of social futures (pp. 182-202). New York, NY: Routledge

Martello, J. (2007). Many

roads through many modes: becoming literate in childhood. In L. Makin, C. Jones Diaz, & C.

McLachlan (Eds.), Literacies in childhood:

Changing views, challenging practice (2nd ed. pp. 89-103).

Marrickville, NSW: Maclennan & Petty – Elsevier.

Seigel, M. (2006).

Rereading the signs: Multimodal transformations in the field of literacy

education. Language Arts, 84(1), 65-77.

Oral Storytelling

I can relate really well with the oral aspect of literacy and only because everyone talked in my family and therefore they had stories to tell! I have lots of memories of being told "family anecdotes, tall tales, and embellished legacies" (Cline & Necochea, 2003, p. 126) during long car rides, during camping trips, during meals with families, or sneakily eavesdropping as my mom and her sisters gossiped about other family members or simply reminisced about their own childhood!

Reflecting on these memories, I believe that stories and the act of storytelling allowed my family and I to spend time together (Sabnani, 2009). My sisters and I always gathered around grandparents, aunts and uncles and older cousins who were willing to share stories of their past. We were never discouraged to listen even when subject matters were serious or had negative outcomes and any questions we had were always answered - the stories were very much interactive too! I especially liked hearing stories which were accompanied by crisp and faded black and white or sepia coloured pictures and most especially if the people within those pictures were still alive or are the storytellers behind the captures! Sabnani states that “pictures also stimulate imagination and the art of reading between the lines…They aid memory…encourage curiosity and creativity, particularize situations, provide temporal links, and extended text” (Sabnani, n.d.). As great as the stories were told, having pictures to accompany them enriched and created more nuances to the stories itself. It was also interesting to hear different versions of stories which I now see as allowing me to understand “the possibility of multiple perspectives” (Sabnani, n.d.) and perhaps, also taught me to think critically about stories and situations I was immersed into.

I heard many stories but I never attributed the act of storytelling to my interest in reading or writing in later years. I wonder if my parents (and other adults in my childhood) knew that what they were doing in telling us stories was actually setting a good foundation for our future in literacy?

In my experience, I don't remember being too affected by the discrepancies between my home literacy practice and school literacy practices. However, I also believed that reading and writing was something just done in school. At such a young age, I believed I conformed to this idea and when I had some challenges writing stories during “creative writing” periods I never thought that it was because perhaps, I excelled better in oral literacy practices, or other modes of literacy. I didn't struggle with the conventional ways of literacy; however, I always felt that I was never good enough as a writer or I wasn't creative enough because I couldn't write the way my teachers taught and 'encouraged' me. This leads me to think about how (cognitively, emotionally, spiritually) limiting conventional literacy practices can be for children who practice literacy beyond reading and writing. Children are restricted in their ability to express their thoughts and ideas and they can be profoundly silenced when the literacy practice(s) that they connect with are not honoured in their classrooms. As an Early Childhood Educator I find that I can easily experience literacy with children in varying ways - oral practices is almost always included. Is it the same when children enter elementary school or is it harder to uphold the other ways of engaging in literacy (or children's varying home literacy practices) because of the curricular mandates of teaching children to read or write a specific way?

References:

Cline, Z. & Necochea, J. (2003). My mother never read to me. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 47(2), 122-126.

Sabnani, N. (2009, July). The Kaavad storytelling tradition of Rajasthan. Design thoughts, p. 28.

Sabnani, N. (n.d.). Designing for children: with focus on 'play and learn'. 'Homing' in with stories.

Literacy as Social Practice

Globalization has magnified the world and we are able to see

more and more societies with diverse groups of people with varying cultural

beliefs, values, traditions and practices. This diversity is also very close to home existing in the

classrooms/centres with the children, families and colleague interacting and

working together. From here, we

can see the different learning styles of each person and this provokes the

necessity of understanding how different social contexts, to which each

individual is embedded in, affect how s/he represents, communicates and

interprets the world. Literacy

enables us to make our representations, communications and interpretations

palpable. As educators of and

learners with children, if we cannot acknowledge that literacy practices are

different for all children we are not only ignoring aspects of their mental and

emotional strengths but we are also suppressing their overall development. To successfully and ethically support

children’s literacy learning, it is important to “understand what reading and

writing goes on in the home” (Barton, 1989, p. 1) and to understand what values

are placed in such practices which motivate or discourage children to

participate.

Barton (1989) speaks about the “literacy brokers” (p. 7) in

children’s lives and these could range from the parents, older siblings to the

grandparents, aunts and uncles all of which interact and engage in various

literacy related practices – “reading and writing…listening, viewing and

drawing, as well as critiquing” (Jones Diaz, 2007, p. 32). These relationships are important to

acknowledge because significant learning occurs in these interactions. “[R]eading

and writing [are] not just an individual affair; often a literate activity

consists of several people contributing to it” (Barton, 1989, p. 7). The narrowed view that literacy exists

in isolation or that it is a “skill” (Comber & Reid, 2007, p. 46) that can

be taught and eventually mastered within just reading or writing places little

value on the learning that does occur in children’s social contexts and

therefore restricts the possibilities of different literacy experiences that

children can use to make meaning and to express themselves.

With all this in mind, I question how we respond to immigrant

parents/families who are resistant in sharing their literacy practices at home

for fear of being judged as not “doing enough” or because their priority is to

have their child master reading and writing in English? How can we honour their wishes and also

ensure that we are not imposing our emergent ways by wanting to know how

literacy is practiced at home?

Reference:

Barton, D.

(1989). Making sense of literacy in the home.

Jones Diaz, C.

(2007). Literacy as social

practice. In L. Makin, C. Jones

Diaz, & C. McLachlan (Eds.), Literacies

in childhood: Changing views, challenging practice (2nd ed. pp.

31-42). Marrickville, NSW:

Maclennan & Petty – Elsevier.

Comber, B., & Reid, J. (2007). Understanding

literacy pedagogy in and out of school.

In L. Makin, C. Jones Diaz, & C. McLachlan (Eds.), Literacies in childhood: Changing views,

challenging practice (2nd ed. pp. 43-69). Marrickville, NSW: Maclennan &

Petty – Elsevier.

Thursday, January 27, 2011

Emergent Literacy

In this week's reading on Emergent Literacy, I am reminded of an activity I facilitated where children created their own storybooks. It all started when two Kindergarteners were very interested in pretending to be teachers leading a literature circle. They "read" the books by way of explaining what they saw on the pictures of each page. They provided a very creative and unique take on books about the fall season, dinosaurs, and even the ones that were Disney inspired.

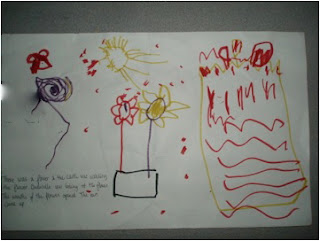

With their permission I recorded their stories and played it back to them. They expressed a great deal of excitement and pride, wanting to have their peers listen to it as well. From here, I presented the idea of writing these stories out and them drawing the image they wanted to accompany their descriptions. I sensed a little bit of hesitation but one of the children wanted to make a whole different story instead. Er. wanted to draw her pictures and wanted me to write out the words providing a story for the images she drew. Em. followed suit and began her own little story book as well. I took the lead from each child who went as far as telling me exactly where they wanted their words written out on their picture! Once I completed their storybooks they were quick to share with their peers who listened intently. This motivated five other children to create their own storybooks, which they also shared with their peers, teachers and parents. (I have provided a few examples below)

It is important to note that during these moments, particularly for the children who were beginning to read and write, they were encouraged to write out their own stories; however, because the interest was on drawing and oral storytelling, I followed this lead instead. Some of the older children practiced their writing skills when they wrote out their names and they also practiced their reading skills as they read out their stories. Most of the younger children (3- and 4-year-olds) didn't "read" their exact words on the page but I believe that because they were really interested and took great pride over their work, they were able to remember the main content of their stories and therefore, told their story to their liking. Literacy was clearly at work during this experience. The children's interest and motivation to read, tell stories, and draw helped create unique storybooks, all of which create a significant foundation for their literacy development (McLachlan, 2007, Yu & Pine, 2006).

As expressed by McLachlan (2007), when an opportunity like this is presented to children in their early years the impact it has on their later literacy is significant. What I learned from this experience is the importance of following the children's lead and how this sustained their interest in the whole activity. Each child had a connection to their work and this allowed them to keep drawing, keep telling me stories, keeping telling their peers stories, and so on.

Emergent literacy was evident in the way the children and I engaged in the given literature experience - looking and reading books, reading the stories based on given images, creating images and attaching stories to it, oral storytelling, etc. - but I know full well that emergent literacy is not limited to this. The children were proud to share their creations with their parents/families and when I conferred with them about this activity, the consensus was that each child had rich literacy experience at home - trips to the library, reading to other siblings or stuffed toys, engaging in play where children pretended to be teachers leading circles or doctors writing out prescriptions, reading before bed, etc. However, I wonder about the children that do not have literacy experience of this kind and perhaps are not engaging in any form of emergent literacy as describe in our readings. I wonder whether this literacy experience excluded children who do not express themselves through drawings and artwork or are not comfortable with the oral feature of the storytelling that occurred in this activity. Unfortunately, I wasn't able to recognize these children and now I wonder how I could have accommodated them. It is wrong to assume that they are lacking within their literacy development because they did not engage in the literacy experience. How then could I have supported the "literacy strengths" (Evans, 2001) that I know they had? How could I have created a space which also invited these children who were not drawers and oral storytellers? There were children who did not create storybooks who were interested in listening to their peers who played authors/writers/illustrators. What could I have done which allowed them to engage beyond just listening? Is listening enough of a literacy experience for certain children if this is all that they are doing at home and/or interested in engaging in?

This is the son, boy. This is father. They are on a ship and they are watching the mice climb up the stairs. They thought the stairs were slides on a playground but it wasn't. These are the mice.

This is a tractor. This is a machine. This is a fire truck. It sprays some water. This is the recycling depot. It is where they take all the garbage.

This is a car. It is carrying a bag. The car wasn't too strong. This is a fan. The fan is blowing the car.

This is a door and the door broke - it just fell over by itself. And so they have to build a new door. They have to build a new house because the tractor was shooting some balls to the house.

This is a big ship. The wind was blowing the ship but the ship didn't go. The ships shoot some balls in the ocean and it went pop! This is the ocean.

A's storybook:

There was a flower and the castle was watching the flower. Cinderella was looking at the flower. The mouths of the flower opened. The sun came up.

There was a girl that lived in the castle and her name was Sleeping Beauty. Sleeping Beauty was watching the flower growed and it growed and growed. So while she was sleeping the flower growed and growed.

The princess named Ariel and her prince named Eric. Ariel was first a mermaid and then she turned into a princess. Eric fell into the sea and Ariel caught him. She was watching him and she saved him onto the beach where his dog was

There was Cinderella's sister and her name was Claudia and she turned into Cinderella. Then sunflowers grew and then there was a wall growing.

revisiting the storybooks with the children

References:

Evans, K. (2001). Holding

on to many threads: Emergent literacy in a classroom of Iu Mien children. In E. Jones, K. Evans & K. S.

Rencken (Eds.), The lively kindergarten:

Emergent curriculum in action (pp. 59-74). Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Makin, L., Jones Diaz, C., & McLachlan, C. (Eds.). (2007). Literacies in childhood: Changing views, challenging practice (2nd ed.). Marrickville, NSW: Maclennan & Petty – Elsevier.

Yu, Z. & Pine, N. (2006). Strategies for

enhancing emergent literacy in Chinese preschools.

Los Angeles, CA.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)